The world of today has little to do with the world in which I started working.

When I started my career, I did not have a mobile phone. Nor a PC on my desk actually. A fuel-effective car burnt 12L of diesel for 100km, recycling plastic sounded as aspirational as recycling toilet paper, and “social media” was meant watching the news with your mom and dad.

For all the changes since then, I can see two elements in the context of today that really transform the way we do business: transparency, and anxiety.

Anxiety and transparency – a new context.

Transparency is a technology change. It means I have instant access to more data and knowledge than Einstein or Descartes even dreamed of. It means that everybody has access to more data and knowledge. Transparency is insane… Recently the BBC was able to identify the authors of a killing in Cameroon based on a single video. A collaborative team used Google Earth to track the location of the video, used the shadows on the video to calculate the position of the sun and to date it, recognized the army corps involved by comparing the uniforms of the soldiers on the video to a database, and finally identified the 3 guys responsible for the killings based on the posts on their Facebook accounts that week.

Transparency is also a cultural change. People at Google explained it to me in a simple phrase: “because we can know, we want to know”. My mother had no idea where our potato came from. I now can know where the potato I buy at the supermarket comes from, so I want to know – and I chose the most local I can find. In turn, producers work hard to facilitate traceability. This feeds an acceleration of data that exponentially nurtures what I know and what I want to know.

Anxiety…

The mindsets of our societies follow anxiety waves, that were identified by professor Helmut Gauss at the end of the 90s. Collectively, we go through a gradual increase of anxiety for about 20 years. It then peaks, and anxiety goes down. We learn to trust the future, ourselves, each other again. Until anxiety gets to a low and starts climbing again. Anxiety waves are connected to long term economic cycles – the Kondratieff cycles. And they seem to not follow them but precede them.

They have profound impact on our societies – shaping fashion, design, culture, politics.

In periods of low anxiety, we deal well with differences. Trust dominates and smoothens social relationships. Men and women embrace closer values and codes. We free ourselves from social norms. Exchange becomes a key value. The swinging 20s, but also the 60’s, the hippie movement, the Vietnam peace protests and the legalization of birth control were all in low anxiety period. So was the election of Barack Obama, the Dove campaigns for real beauty, the rise of the internet and of social media.

In periods of high anxiety, we struggle with differences. We resort to conflict. We seek reassurance in norms, traditional principles, and set identities. The 30’s and 40’s were high anxiety periods. The late 70’s and the 80’s, marked by economic crisis, the beginning of high unemployment, terrorism in Europe, were high anxiety periods.

The work of Helmut Gauss suggests we have entered a high anxiety period again. The election of Donald Trump, the rise of European populism, movements against immigrants and against abortion confirm we get back to more traditional norms. Did you notice Tinder is of the past already? Technology only facilitates the move, as we all get separated into our own algorithmic bubbles, where we only see what corresponds to our own world view. And the theory suggest we are only in the middle of the wave. Expect 10 more years of anxiety and doubt.

These two elements of context transform our business because they bring in three shifts that shake the foundations on which “BIG” business rests.

One, the rise of a me-world.

We deal with the most empowered generation that ever walked on the planet. The reality, but also our culture, is that we can choose our lives. Young generations do not receive (TV programs, education, salaries), they want to make. They develop the content they watch on YouTube, they craft their own education through Mass Online Courses – so much that MBAs struggle to recruit. They want to create their own jobs – the dream job of today is entrepreneur, not marketer at a FMCG company. Knowledge and anxiety lead you to take control and do your thing.

Two, connected awareness.

Because we know, we want to know. And because we know, we make connections. We understand the connections between our modes of consumption and the state of the planet. We understand the connections between the brands we buy and the companies that run them. Already in 2014, Coca-Cola faced a boycott as young people refused to buy its brands because it was closing a plant and laying off workers, but people are also ready to buy a brand because its parent company has a positive action on society… They were simply connecting a brand, and the responsibility of the corporation behind it.

Three, new power.

The term was coined by Jeremy Heimans. It reflects the idea that power today is shifting. Whereas old power was centralized, authority driven, with high specialization and loyalty at its core, new power is participative, open source, sharing, based on short term affiliations, transparency and a “maker” culture. Think the election of Barack Obama or Emmanuel Macron. Think the #meetoo movement. New power is the child of transparency. It defines a world where just a few consumers can kill a brand, because reputations are out of the control of businesses.

Three shifts that challenge “BIG” business.

These 3 shifts – a me world, connected awareness, and new power – fundamentally challenge the way “BIG” business operates.

BIG food companies have been struggling for years because people want to buy local food they understand, from small companies around them. Craft beer explodes. Small baby food brands explode. Big restaurant chains have been disrupted by the preference for smaller players, or for people with a smart, specific promise – thing McDonalds vs Five Guys. Think Ben & Jerry’s disrupting the ice cream industry, being bought by Unilever, and being now disrupted by a smaller brand called Halo Top just because they were smart enough to understand first that people want pleasure with less calories.

Big companies reflect old power. They are centralized, controlled. They build simple, one-size-fits-all propositions that clash with the “me” aspiration of being unique and individual. It might be in what they offer and they uphold – think of big retailers like Tesco or Asda, who find it impossible to challenge the decentralized and individual experience that online shopping can deliver. Or it might be because despite flashing new power values, they still operate along old power ways – think Samsung, Apple, or Uber. It’s hard to be a big company in this world.

A part of the answer from the “BIG” world has been “purpose”.

That started with Dove. Remember: they show you with loads of emotions how much our vision of beauty is distorted. They assign an enemy to it. The fake ideas we have of beauty, largely driven by the beauty industry. Read: by L’Oréal, which is the brand Dove was pitted against. Then they offer you a beautiful idea to buy into: “every woman is beautiful”. An idea that you could challenge, but that rallies the people who want it to be true: that’s why it’s powerful. And finally, they offer you a product that is the embodiment of that idea: beauty products that nurture who you are, rather than trying to change who you are, because it contains nurturing cream.

That kind of purpose is genius. Because you take your own brand history, and you elevate it to make it meaningful. You don’t need to do much more. You do need to do a bit – like create a foundation that will help young girls build a better self-esteem. You can do it really well – the Dove foundation has reached millions of girls, and really helped them. But amazingly, you don’t need to change anything in your business model to become a purpose brand. Which is cool, because it allows many companies to do something kind of useful, without much effort except for savvy marketing and smartly used donations to a cause.

Sadly, for ad agencies at least, this kind of purpose work is deeply insufficient.

Dove is struggling today – after years of success. And many of the brands who join the bandwagon today struggle. This is because they use purpose as a mere marketing tool – and that is not sufficient to deal with the new context that “BIG” business is operating in.

Because of transparency, you can’t come up and speak about a purpose without it being REAL. That means, it makes a significant, measurable difference. That also means, it’s congruent, logical for your business, not some kind of borrowed topic.

Because of the me-world we live in, you can’t build a purpose without being COLLABORATIVE. People do not expect a business to do it all, have all answers. They feel they can, and should be part of it, if it’s good.

Because of connected awareness, you can’t build a purpose that’s not DEFINING. That means, it will impact everything you do in your business, showing commitment.

Because of connected awareness and of new power, you can’t build a purpose that’s not POWERFUL. I mean here that that purpose needs to address the most potent issues that you face, not side challenges. Coke can battle for recycling, but as long as they don’t tackle obesity, they will struggle.

Maker brands and purpose as a business tool.

However, when a purpose is all that, it becomes incredibly powerful, because it becomes vital.

Vital to the people outside the company, who see you do something truly useful and engaging for them.

Vital inside the company, because that purpose becomes a tool to make decisions, to create focus, to rally forces in one direction.

Purpose becomes a management tool: it’s the simplest way to ensure a few thousand people across a handful of functions and dozens of countries all know why they come to work and agree on what is really important. It’s the simplest way to ensure that that what they do delivers what all the stakeholders of the company think is important.

This is why we all love so much the work of Patagonia. They want to preserve the beauty of nature’s work, and it’s real – they are selling products that are better, and they put real money into environment preservation.

- It’s collaborative – they work with their suppliers, but they also offer you to come up and bring you old jacket to recycle or repair. A brand is a relationship, and in a relationship both parties are supposed to take an active part!

- It’s defining – their R&D, there stores, the internal culture reflects that purpose.

- It’s powerful – the apparel industry is the second most polluting industry on the planet, so they tackle the real problem.

Look at Dove, it’s still real, but it’s hardly collaborative – you are not invited to help. It’s not defining enough – they still sell whitening cream and it does not impact much of the R&D or the internal culture. And it has lost much of its power – in part because they actually did their job. Our culture has become more acceptant of diversity in beauty. In part because there are a lot of other issues related to the beauty industry that we expect a leader to cover – from plastic pollution to real women’s empowerment, and because they failed to turn their purpose into a tool that would unite the forces of people across functions: it’s less powerful, and it’s hardly defining.

The job for Dove, and the job for everything that’s BIG, is to create a vital purpose. Because when BIG do that, BIG turn their power – which people challenge because it goes against their own “me” world – into a tool to build the world that people want. And this defines the brands that people want to buy.

In a world of me, of connected awareness, and of new power, people want to buy brands that help them build the world they want. That’s why we call them “maker brands”. Because they make sense, they make things move, they often make your day and, they make your world better.

Your own little world, by solving your practical issues and making you feel good. Your bigger social world, by helping you integrate in a group, and signify something to others. Your much bigger world, by taking political or environmental action.

When you have a vital purpose, that’s what you achieve: you have a tribe of people whom you genuinely help to build the world they want, and they make you thrive. That’s the power of Nike. They speak of empowerment, they sell you great shoes that make you run better, they push the idea of achievement for anyone, and they go against the Donald. When your business works on a vital purpose, what was a liability as a BIG business becomes an asset. Because of your size, you can make a difference, and serve the higher aspirations of transparent me-world.

The question left is: why don’t we all build vital purposes? Why don’t we all do maker brands?

The reason is called: the empathy gap. Empathy is the stuff of legends.

When you say the word in a boardroom, you sound like a tree hugger. But empathy is not a soft, my-little-pony skill. Effective empathy requires us to connect both cognitive empathy to rationally understand the reality of others, and emotional empathy to feel what they are feeling.

Maker brands: bridging the empathy gap.

Interest in empathy grows. There are 30 million answers to the query “empathy in business” on Google. There are good reasons for this. Empathy raises the levels of dopamine and of oxytocin in your brain – in other words, it makes you happy. In times of anxiety, it’s useful. Empathy is also good for business. Research shows waiters with empathy get 20% more tips. L’Oréal sales people with the highest level of empathy sell almost $100.000 more than their colleagues, and debt collectors with empathy collect more debt. Empathy makes better teams and better leaders. Six out of 7 employees would take less money for an empathetic employer, 77 % would work longer hours.

It’s not that empathy makes business better, empathy really is the base for business. Business is about understanding the needs of people and serving them better. That’s empathy put in practice.

Small companies are empathic by the nature of their organization. They are run by people who work in their living room, use the products they sell and try to make these products better for clients they talk to. They genuinely understand the world of the people they talk to, and they try to make things that make sense.

BIG business often works differently. We work in offices. We talk about “consumers”, which is almost insulting as if you were talking about walking wallets. At the least it’s un-empathetic, if you allow the word, because it puts a separation of nature between the person who buys and the person who designs, like we were not both real people, like I did not consume too. We delegate the understanding of these “consumers” to researchers who summarize their learnings into “insights”. We don’t listen to the social realities of the places where we live, because social realities don’t have wallets, only consumers do. We don’t use what we sell because “we’re not the target”. We often actually don’t fully understand what we sell, because it’s too complex and it’s the job of the R&D guys anyway. We don’t fully understand the impact of what we produce and sell on the communities, the societies, the planet we live in because it’s too complex and it’s the job of the sustainability guy.

That’s really understandable. That way to get organized has led to great things too. If you build a rocket to go to Mars, it’s an effective way to work. But in a me-world, in a world of exponential transparency, in a world of anxiety and distrust, that empathy-gap is what makes BIG shake further.

It’s a gap of human understanding. In a me world, when I sell baby food, I need to understand why parents choose to have children, and the challenges of parenting today. Not just baby feeding.

It’s a gap of societal & cultural understanding. In an anxiety driven world, when I sell beauty products or women’s apparel, I need to understand the meaning of femininity and how it evolves. Because you don’t market lip gloss in the same way before and after Harvey Weinstein.

It’s also a gap of technical understanding. In a transparent world, when I sell water, wheat or milk I need to understand where they come from, and what impact their production and their packaging has on the planet and the farmers or communities that are involved.

Bridging the empathy gap is not difficult. But it’s a change of practice. It’s a choice of focus.

When we work with the users of a brand whom we do not know well enough, we take the client team to spend time at their homes. We cook a meal together. We use their bathroom. We play with their kids. We talk about the human fabric that is the context of their brand. It’s incredibly simple. But when a marketer who comes to work in a BMW spends 5 hours in a slum in Bangkok, or in the apartment of an immigrant family in Lyon, his ability to produce a product innovation or an ad that effectively serves the lower-class people in his country increases dramatically.

We worked on products for aging people for a pharmacy company and we had the team wear aging suits. It transformed their level of empathy and changed the way they even design packaging. Ford has a “belly suit” to help engineers try their cars, so they understand how people feel in them when they are obese or pregnant.

Facebook has 2G Tuesday, when people in the office work with the internet speed of a 2G. It’s an amazingly easy way to let them feel what millions of people feel when they use Facebook in the real world, not in Menlo Park.

When we built a “nature inspired” brand of infant formula milk in China, we talked to doctors and sociologists who explained to us how society was changed by the lack of nature. How Chinese kids are scared of ants. How parents think playing with leaves is dangerous. Then we took the Chinese brand managers to a farm in Ireland. Together with the sourcing team, the R&D, the sustainability guys. Nobody in the Chinese team had ever seen a cow. They touched the grass. They saw the crazy work the Irish farmers do to improve the quality of their milk, the 13 different types of crops that the cows graze in to balance their digestion and reduce their carbon emissions. They understood why the carbon footprint of Irish grass-fed milk is half that of milk coming from European places where the cows eat soy in their sheds, year-round.

They returned home and made some connections. Carbon footprint. Nature deprivation. Grass-fed. Strong grass. They did it together, the sourcing people, the brand people, the R&D. They made some hard choices – they moved their milk supply from Germany to Ireland, so they could support better stories. And they built a brand that rocked the entire market – because they integrated in their stories the societal and technical empathy they had built.

When we build empathy for people, for the society they live in, for the technologies that shape their lives, then we think, create, and design brand work that makes sense for people. We make brands that don’t have a purpose, but that serve a purpose.

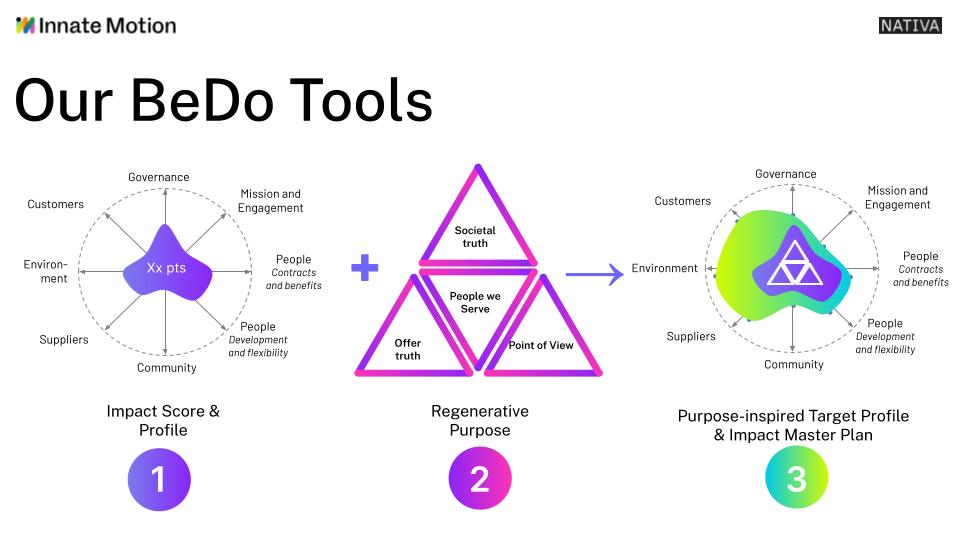

To build empathic, maker brands, we need our marketing and business toolbox to change, and I want to share with you three empathy-based tools that can totally transform the way we run business.

Three tools to bridge the empathy gap.

One, move from consumer thinking to ecosystem thinking.

We started to work on Axe in 2014. At that moment growth was slow. The brand was running sexist ads that guys found funny, but that had stopped driving the business. We were asked to help rejuvenate the brand by finding it a purpose. We talked to guys from half a dozen countries. But then we also talked to women. And we explored every human and societal theme that had to do with masculinity. We talked to NGOs who were working on causes such as rape prevention, education, bullying aid. We looked at movies, at series. We looked at what made the male culture – the age of first sex, the culture of porn, Tinder.

And we figured that there was a disconnect between what men said – they want to be cool guys, respectful of girls, engaging in real relationships, and what society as a whole pushed on them. A societal view of masculinity that did not offer a real alternative to the old-fashioned macho man. So as soon as they were in a group, the nice guys were back into primal behavior.

We thought of Axe as a brand that served an eco-system. When you are one of the biggest male grooming brands in the world, thinking that the people you should focus on are a few millions of 15-25 testosterone gorged young males is preposterous. Like an infant formula brand serves the parents, the child, the doctors, the people in charge of public health, and needs to be designed as such, Axe serves men, women, NGO workers, educators, because it plays a role in defining masculinity in our society.

Brands define culture, just as much the movie industry defines culture. It seems hard to say, many would say they just reflect culture. But think of Black Panther, the first Marvel movie with a predominantly black cast. Does it reflect a culture that now genuinely makes a bigger space for minorities? Certainly not. But it captures a readiness, it amplifies a movement.

When I say brands define culture, when I talk about serving an ecosystem, I don’t mean it as a burden and a responsibility. I mean it as an opportunity. Black Panther took an idea whose time had come – that of black empowerment. They served an ecosystem of cinema viewers, activists, artists, NGOs, and turned that idea into a business driver, making the film the highest- grossing super hero movie of all time.

We have convictions, but the point here is not even about being moral. It’s this: if you recognize you serve the higher benefit of a full eco-system, that full eco-system serves you too. You get buzz, free media, word of mouth, visibility, better recruits…

Eco-system thinking led to the “Find your Magic” story by Axe. To the purpose of taking men beyond the primal views of masculinity that limits them. A purpose that takes Axe back into growth, because once you find your magic, you need to work on it – and that’s what their products are for.

Two, move from a logic of a working for people, to a logic of working with people.

The Axe work was not done in a vacuum. It was not research based in the classical sense of the term. We went to see guys, and we told them – we want a better Axe. Would you like to help? We went to NGOs and said – we need help to think better, would you join our sessions? The first part of the work involved them to learn with them. The second, to define the actions. We figured one of the biggest enemies to the change, one we could battle against, was bullying. Because this is when guys, as teenagers, are told “be a man” for the first time, and never forget.

Axe has not decided to act on their own against bullying and brag about it. Rather, they partnered with Promundo, and a few other NGOs, and built programs together. They put themselves at their services, and they knew they could – because their purpose was so vital that they would all benefit.

The most interesting aspect of the work, however, had to do with who was involved. The global Axe team at this time was led by 4 South American guys, who actually embodied pretty well the values of primal masculinity! The move of Axe was also their move. Working with people, they accepted to work as people, challenging their own beliefs.

The only thing we did was creating a context of trust, so this could be done safely. In the end, it’s about the people in a business acknowledging their vulnerabilities. It’s about acknowledging that we have issues, that we don’t have all the solutions. Then only we can truly innovate. For Axe, that transformation capability was lifesaving. Eighteen months year later, the #metoo movement would have killed the brand.

Three, move from claims, to stories.

Claiming is become core to marketing – across categories. Ariel cleans better. Evian is more balanced. Chipotle does not contain antibiotics. But claiming is not empathetic. It says “listen, I have it right”. In a world of me and of distrust, you speak in the desert.

Stories are the language of empathy. Working with a food brand, we tested the claim of “the brand helps 100 farmers transition to organic”. It created doubts. One hundred? Is it good? Too little? But when we let a farmer whom the brand was helping in his transition to organic tell his stories, and then another, and a third, there is no doubt. And these stories are shared, because they are real. Claims are not shared.

Many brands have product architectures, we create stories architectures. What stories do you tell to reassure your clients? To inspire them? To convince them of your performance? To unite them into a community?

With a brand of margarine, we figured that the biggest fear of the families buying the product was how processed the product is. Margarine is hyper-processed. You can’t change that. But so is every oil we consume, except for top grade olive oil, because if you press any fat fruit or grain, the oil you obtain is acid, bitter, just inedible – until you have chemically refined it. We could not go against that. But we started telling the story of where the oils used in the product came. In the country where the product was sold. In small farms, in beautiful landscapes, where farmers struggle, but produce great oils. In poor villages where selling sunflower seeds means development, schools. And suddenly margarine did not feel scary. It became a produce of the land – which it is.

In the same time, we built stories of inspiration – showing how baking (the core usage of margarine) was a way to bridge the generational gap in families; stories of performance, talking about the health impact of margarine – vegetal fat is much better then animal fat is for us, and it’s important to remind how rich it is…

Old time marketing looked at a brand as a well-guarded store with a single entrance, and the job of communication was that of a salesman; bring people to the front door of the store with a single pitch, and then the rest is up to luck and good will.

But today the spin-doctored pitch of the salesman has turned into cause of distrust. Brands are more like an open farm. People want to see how things are made. What the farm landscape looks like, how the farmer’s wife treats the cows, whether the farmer’s family eat their own produce, and what the farm employees think of it.

In the times of 30” TV ads, there was no way you could share all that.

In the time of exponential transparency and of personalized, online consumer journeys, you can tell all these stories effectively, each to the people who need them and want them. The power of online media is not that it allows reach and has stopping power. It is that it allows empathetic communication, weaving stories into a compelling collection of coherent, complementary narratives that together, define your brand in all its richness.

Stories have power. That’s because they are a human way of communicating. So is business.

A hundred years ago, a young entrepreneur saw dust-poor workers flock into slums around English industrial cities, living in terrible hygiene conditions. He started a business on a simple idea: if you could make hygiene common place, people, cities and the country would benefit. And he would get rich too. That entrepreneur’s name was Lord Lever, and his idea was a vital purpose. It was put at the core of what later became Unilever.

The world has changed but organizing our businesses around vital purposes is more critical than ever.

It only takes one ambition: bridging the empathy gap.

e see this kind of thinking reflected in the shared belief of Walls ice-cream that speaks of ‘Happiness for all’ (and not just the joy of ice-cream); as it creates employment opportunities for marginalized street vendor

e see this kind of thinking reflected in the shared belief of Walls ice-cream that speaks of ‘Happiness for all’ (and not just the joy of ice-cream); as it creates employment opportunities for marginalized street vendor Moyee coffee calling itself Fair-chain coffee uses blockchain technology; so, you can see how the dollars from your coffee purchase ends up into the hands of the coffee grower

Moyee coffee calling itself Fair-chain coffee uses blockchain technology; so, you can see how the dollars from your coffee purchase ends up into the hands of the coffee grower